How the Heartbleed Vulnerability Shaped OpenSSL as We Know It

Table of Contents

Few are the bugs that truly make it into mainstream notoriety. Whether having to do with its unabashedly dramatic name and logo or with little relation, the Heartbleed vulnerability is one flaw that has become a household name.

Made public in April 2014, the Heartbleed vulnerability (formally designated CVE-2014-0160) was a simple coding mistake that left a vulnerability in the heartbeat extension (RFC 6520) of OpenSSL; an open source library providing cryptographic functionality to secure web servers. With over 66% of web servers using OpenSSL at the time of disclosure, two-thirds of the world’s web traffic was compromised by this vulnerability. OpenSSL released a software patch within a week of the bug’s disclosure, sending hundreds of thousands of affected developers and site admins on a patching frenzy.

But the effect of the Heartbleed vulnerability on the developer community did not end with the prompt call to remediate. Like other big-name open source security vulnerabilities that came before it, Heartbleed seemed to generate a climate of trepidation about the use of open source. Much was said about OpenSSL being maintained by a mere two developers (both named Steve) with little funding and practically no resources. Conversations ensued about what would have happened had the vulnerability been in a bigger project. Would it have been discovered earlier? How would it have been handled? Daggers were thrown by the bucket full at the two year gap between OpenSSL’s release of the buggy version and the discovery of Heartbleed therein. And once again a developer-wide conversation began about the reliability of open source and how safe it was to use.

The Heartbleed Vulnerability Lead to Investment in Open Source Projects

By and large, the response to the incident was unanimous in pointing to the imbalance between the widespread use of OpenSSL and the scarce contributions the project was receiving. On the one hand, OpenSSL was running on 66% of all web servers, on the other hand, it was staffed with only two part-time employees. It gets worse. The project had never received more than $1 million in donations per year, and commits and contributors were few and far between too. The history of the minuscule contributions given to the project was well documented by Steven Marquess and lays bare the kind of understaffing and underfunding that some of open source’s biggest projects face.

The catastrophe that was Heartbleed inspired Linux to start the Core Infrastructure Initiative (CII); a campaign matching important open source projects with the financial resources they need. The Linux Foundation invested close to $4 million in the initiative, lending not only funding but also a voice to the cry of the open source community. Facebook, Google, IBM, Microsoft, Dell, Amazon, VMWare, and other tech giants quickly joined, pledging to donate close to $100,000 a year to leading open source projects. OpenSSL was at the top of that list.

From the Heartbleed Vulnerability to OpenSSL Resuscitation Efforts

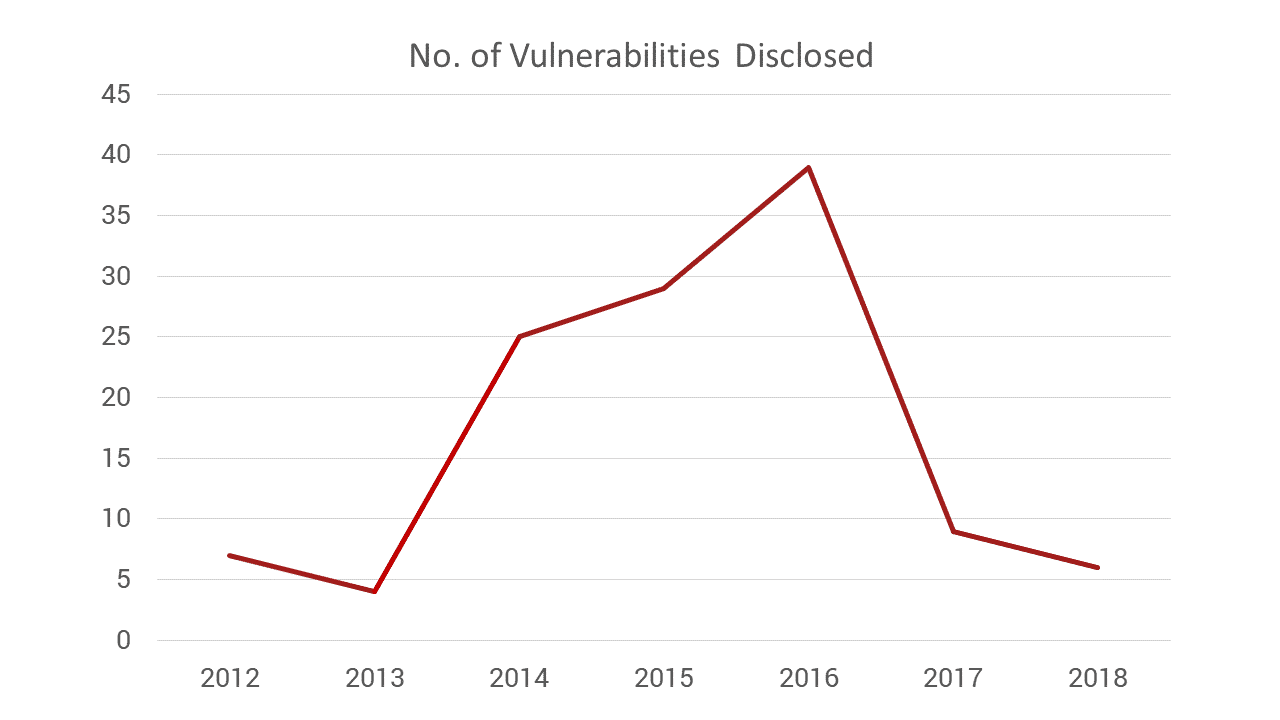

The common trend of open source projects security follows the logic that increased funding and manpower run parallel to an increase in vulnerabilities disclosed. Simply, the growth and maturation of a project, the more eyeballs it gets, translates into closer attention paid to security concerns which, in turn, exposes more security vulnerabilities.

Expectedly, OpenSSL’s security history predating the Heartbleed vulnerability and after the flaw struck followed this very logic. According to Mend research, the number of reported vulnerabilities in OpenSSL was low in the years before Heartbleed (lower single digits), spiking dramatically after the bug’s April 2014 disclosure and in the subsequent two years as the community widened and expanded its activity (29 vulnerabilities reported in 2014 up from 4 reported in 2013).

Interestingly, by 2017 the traditional equation of a better funded project yielding better security came to a halt and 2017-2018 saw a sudden and sharp drop in found vulnerabilities. The sudden decline runs counter to the trend we would expect to see; a consistently quality of vulnerability disclosure as the community widens and expands its activity.

One possible explanation to the sharp decline in vulnerabilities found circa 2017 is that back when Heartbleed hit in 2014 a funding initiative launched on the assumption that the critical bug was the result of the Herculean task placed on the shoulders of OpenSSL’s two developers to single handedly maintain the security and safety of this mega popular project. There was a latent promise therein that more money and more developers would be the solution to all the security woes OpenSSL faced.

The CII relief initiative was born and contributors lined up to ‘save OpenSSL’. The extra funding and added eyeballs resulted in a drastic increase in reported vulnerabilities between 2014 and 2016. There was also the issue of awareness that was suddenly raised to the perils of open source vulnerabilities and the need to manage them. By 2017, however, the hype around the Heartbleed vulnerability had begun to fade, the memory of the critical flaw pushed back into the industry’s collective distant memory, causing the OpenSSL community to revert back to a more lax, lenient, attitude towards code security, characteristic of the days predating Heartbleed.

Another possible explanation to the sharp dip in reported vulnerabilities from 2017 onwards has to do with OpenSSL’s adoption of a proper security policy as part of its 2014 growth and with the influx of funds it received. With more developers reviewing the code as it is being produced and security minded audits incorporated into the development stage, fewer bugs remained unnoticed at release time. Perhaps without intending to, OpenSSL effectively became part of the Shift Left movement.

The Heartbleed Vulnerability was the Watershed Moment

Rich Salz and Tim Hudson started their LinuxCon Europe 2016 keynote speech by stating that April 3, 2014 will forever be known as the “re-key Internet date”. What they were referring to was an industry wide shift in mindset about how open source communities operated and how projects were run.

In its pre-Heartbleed days, OpenSSL had put almost no time into building its community. Its members had never met face to face, communicating solely via mailing lists based on an old Majordomo server. New contributors were scarce due to underfunding. The project had no ability to make, much less adhere to, plans.

In the wake of Heartbleed, OpenSSL’s small developer community met in person for the first time in Germany. According to Salz, that was the first step in creating a real community and a major stepping stone in the collaborative effort needed to both effectively produce new code and find-and-fix existing issues. The project moved the majority of its operation to GitHub and expanded its contributor community by hundreds of percents

OpenSSL set in place long-running support policies for its new projects backed and sponsored by companies like Google and Microsoft, and let its users know that legacy versions will not be supported leaving developers to use them at their own peril. The project’s 1.1.0 release had received support through the end of September 2018. Its successor, OpenSSL 1.1.1 was released in early September 2018 with a commitment to support it for the next five years. This new version is the labor of nearly 5,000 commits made by over 200 individual contributors. 1.0.2, the project’s first long-term supported release, will be maintained through the end of 2019.

The greater lessons to open source projects were manyfold. Amongst them was the understanding that a vibrant community needs a large, expanding and active contributor base. The latter is a necessity not only to avoid development stagnation but also to search for vulnerabilities and provide timely fixes. It was made clear that the value and reliability of projects were directly linked to the level of activity they displayed; the number of contributors and commits it received.

Heartbleed gave open source developers a lesson in discovering issues early on. It became an industry-wide goal to identify security vulnerabilities promptly and publicize their fix days later. Though actual response time is still not where it needs to be, it is progressively shortening and the message is clear: once a vulnerability has been found it must be made public as quickly as possible and a fix for it should soon follow. Not doing so takes away users’ ability to safeguard their code, opening them up to hacking exploits.